Former NFL player LeShon Eugene Johnson, a Haskell, Oklahoma native, is back in the spotlight for all the wrong reasons. On March 25, 2025, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Oklahoma unsealed a grand jury indictment charging Johnson with violations of the federal Animal Welfare Act, accusing him of running a massive dog fighting and trafficking operation. This marks the second time Johnson has faced such charges, raising serious questions about his actions and the broader issue of dog fighting in the U.S.

Johnson, 51, allegedly operated “Mal Kant Kennels” in Broken Arrow and Haskell, where federal authorities seized 190 pit bull-type dogs in October 2024—the largest number ever taken from a single person in a federal dog fighting case, according to the Department of Justice. He’s charged with possessing these dogs for an animal fighting venture and for selling, transporting, and delivering them for the same purpose. This isn’t Johnson’s first brush with the law over dog fighting—he previously ran “Krazyside Kennels,” which led to a guilty plea on state animal fighting charges in 2004, for which he received a five-year deferred sentence and avoided prison time.

The scale of Johnson’s alleged operation is staggering. Court documents reveal he selectively bred “champion” and “grand champion” fighting dogs—those with three or five wins in fights—to produce offspring with traits desired for dog fighting, marketing their bloodline to other fighters nationwide. This trafficking not only fueled the growth of the dog fighting industry but also allowed Johnson to profit, per the DOJ. If convicted, he faces up to five years in prison and a $250,000 fine per count, a steep penalty that reflects the severity of the charges.

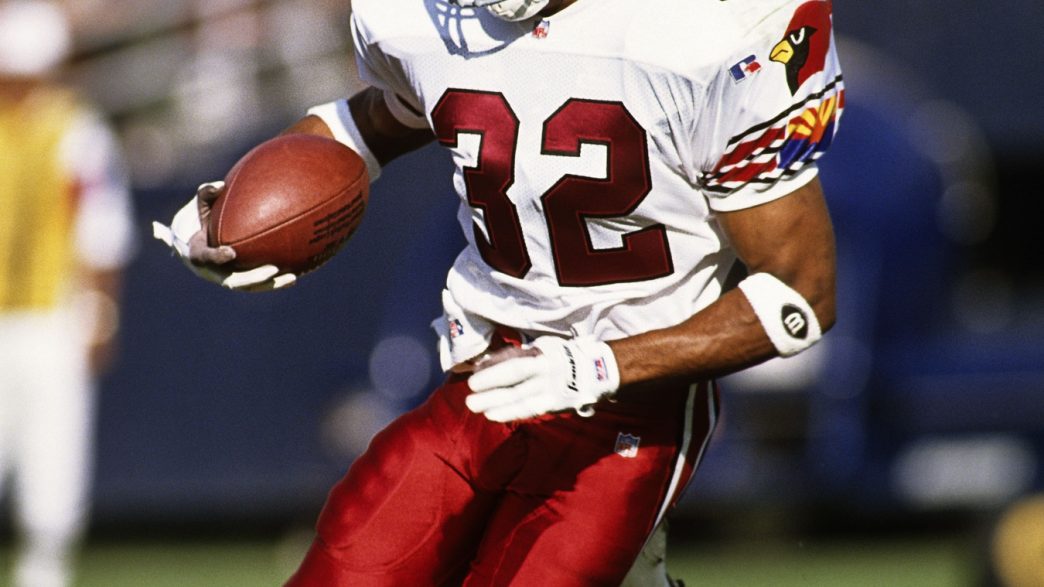

Johnson’s football career paints a stark contrast to his current legal troubles. A standout at Haskell High School, he attended Northeastern Oklahoma A&M College before transferring to Northern Illinois University, where he led college football with 1,976 rushing yards in 1993, earning consensus All-American honors and finishing sixth in Heisman Trophy voting. The Green Bay Packers drafted him in the third round of the 1994 NFL Draft, and he played six seasons as a running back and kick returner, also suiting up for the Arizona Cardinals and New York Giants. Johnson ended his career with 955 rushing yards, 434 receiving yards, 483 return yards, and seven total touchdowns.

But that legacy is now overshadowed by his alleged crimes. The DOJ and animal welfare advocates are taking a hard stance—Attorney General Pamela Bondi called animal abuse “cruel, depraved, and deserving of severe punishment,” while U.S. Attorney Christopher J. Wilson for the Eastern District of Oklahoma labeled dog fighting a “cruel, blood-thirsty venture.” The FBI’s Shreveport Resident Agency is leading the investigation, signaling the federal government’s commitment to cracking down on such operations. Yet, Johnson’s history raises questions about accountability—his 2004 plea didn’t deter him, suggesting either a failure of rehabilitation or a lack of enforcement. Critics might argue the system’s leniency back then enabled his return to this illegal activity, while others could point to the broader cultural and economic factors that sustain dog fighting, often tied to gambling and organized crime.

For now, Johnson’s fate hangs in the balance as he awaits trial. The case not only highlights the persistence of dog fighting but also challenges the narrative of redemption for athletes like Johnson, whose on-field achievements are now buried under the weight of his off-field actions. As the legal process unfolds, the focus will be on whether justice is served—for both Johnson and the 190 dogs caught in his alleged operation.